Consensus decision making sucks

Oscar Wilde once wrote that “the problem with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings”. Possibly there is no greater culprit for these lost evenings than the scourge of consensus decision making, Kim vents.

There, I said it. I've spent a lifetime in groups using consensus decision making, been an advocate for it myself, been to trainings for it and taught other people. It feels extremely vulnerable and cancellable to say: I think it maybe just sucks.

Why?

In this piece I cover four intersecting reasons. Firstly, the prerequisites for consensus are usually seen as a given when this couldn't be further from the truth in most places it's used. Secondly, the insistance we are all equal just means real life class dynamics seep through. Thirdly, this middle management mush tends to create a culture of mediocrity and a fear of specialised labour that weirdly ends up being anti-worker. Finally, feminised labour is somehow even more taken for granted than in wider society and women and femmes end up doing all the work while men have somewhere to go argue with each other. Let's get into these in detail.

Reason 1: the prerequisites for it are rarely met

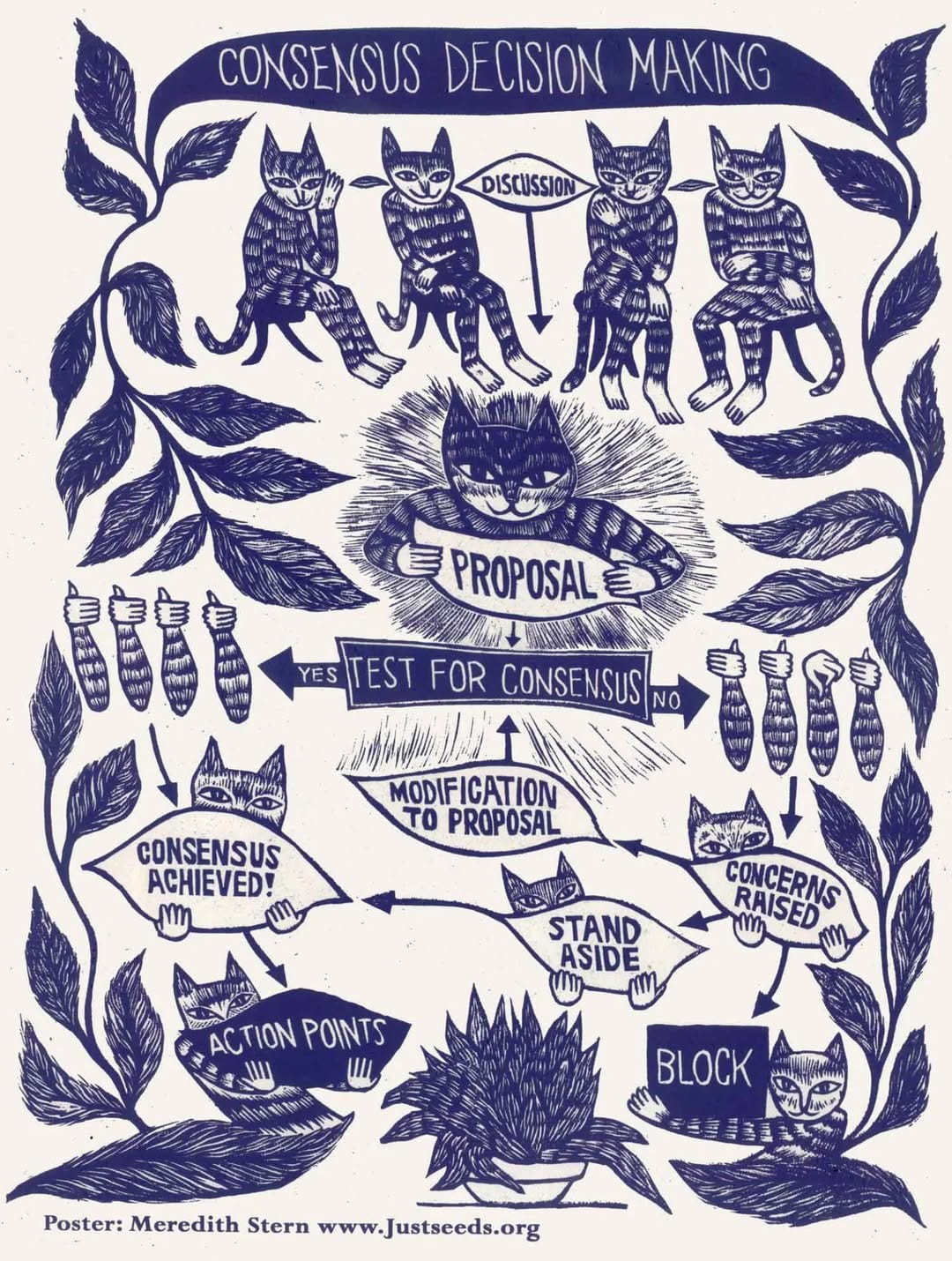

Consensus is great when it's there and it's a powerful thing to aim for. “Consensus decision making”, as a way to run meetings, is a completely different beast. The idea of consensus decision making is basically that we can get some people who don't know each other very well, and who may disagree, through a meeting process no-one is really trained in, enjoys or understands, probably in a cold community centre on a weekday evening, come to an agreement on something contentious under time pressure while someone takes minutes. You can download this in flowchart or illustration form, such as the beatiful one below. Somehow, this is so sensible an idea we need to use it as the backbone to an entire movement. Oh how I wish it were so.

As a default cultural expectation imo it sucks. There's loads of places where we do use consensus without really thinking about it: running a household, in intimate partner relationships, in small groups around personal healthcare, going to protests or on demos with a group of friends, and for that matter just going to the pub. Essentially, any situation in which people have roughly equal investment, already know and trust each other, and are doing something difficult, intimate, or life sustaining with each other. In each of these cases there's a real need for it, and I wouldn't feel comfortable without it either.

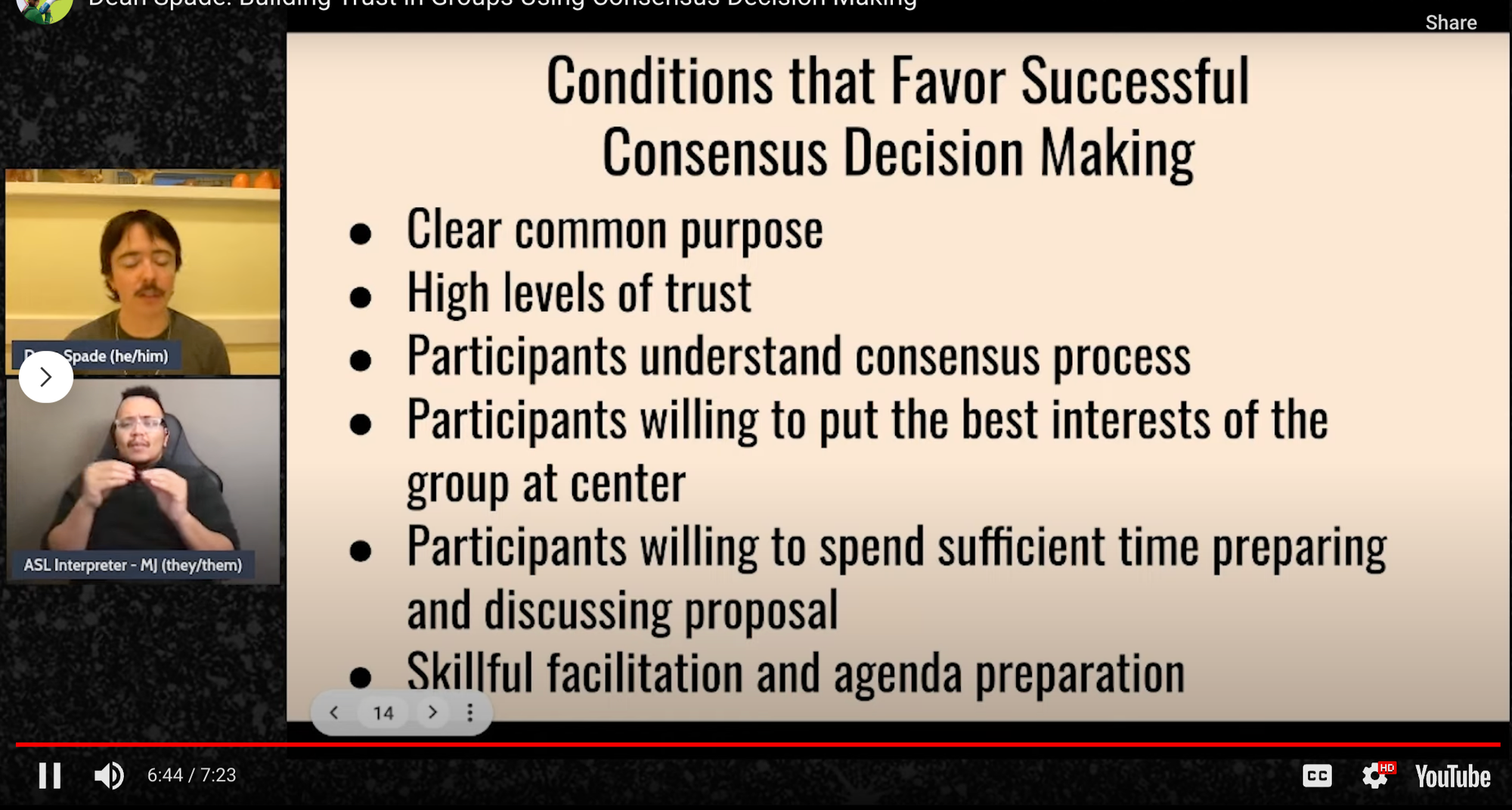

Outside of that though I'm now increasingly convinced that consensus, as it is practiced in the communities I've used it in, is just getting in the way. I am a big Dean Spade fan and think he is one of the best writers on mutual aid, but this slide from a video series I watched recently inadvertently sums up why I think it sucks: it's frequently used in situations where none of the things on the list are true. And we have to stop pretending they are!

In my experience of activist groups, there is no clear common purpose, and time is not made to decide common purpose. They generally consist of a few existing relationships and friendship groups mixed in with a few relative strangers and friends of friends “vouched” for, and so can't be described as high trust environments, even while people in the group love to insist they are. Usually no-one has had any formal or informal training in consensus process, and space for this training is not made. Proposals are rarely written down formally, minutes and action points are seen as an afterthought, and there is no culture of meeting facilitation. There is never a project plan. People have vastly different financial and structural investments and accountabilities. The beautiful flowchart bears no resemblance to what actually happens. Everyone's supposedly read The Tyranny of Structurelessness, but seemingly has learned nothing from it.

Rather than talking about these things and trying to establish trust, train people in consensus decision making, being honest about the internal friendship groups and cliques within any given group, and making time to mutually agree common purpose, instead we just kind of pretend all these things are true – or worse, coerce people into trusting before they're ready – and then get surprised when people fall out with each other or burn out. It feels truly back to front: rather than arriving at consensus through a long term commitment to getting to know each other and exploring the territory the group wants to, we kind of assume that if we run our meetings a certain way everything else will magically get fixed.

I used to think that this was all just “people doing consensus badly”, but after 20 years in these kinds of circles I think it's just materially what big-C Consensus is, in practice. Maybe I've had a load of bad experiences, or been really unlucky, or am part of the problem, but the more I talk to others who have bounced off activism, the more I find this central insistence on the One True Organising Structure as a common factor in souring people to movement politics forever.

Consensus, in its most basic sense, gives everyone in a group absolute rights over everyone else's ideas and actions. Membership of any group you care about is typically a pretty significant part of your life and can be vulnerable and difficult at times. Given how many of us are struggling with trauma, our own bodily autonomy, various stages of transition, current or past abusive relationships, housing insecurity, and so on, how are any of us meant to feel safe in this setting? I've seen the first veto (or perceived veto) causing the end of groups so, so many times, and I think this is why. It means you are playing No Limit Texas Hold'em for every single issue in the group: all the chips are on the table, nothing is held back.

Reason 2: middle management abhors a vaccuum

Without this pre-existing trust in place, consensus decision making paradoxically creates a structure where no-one trusts anyone, where every action anyone takes is suspect and needs scrutinising, and decisions are frequently made and then overturned. As groups grow, each individual has less freedom to act, and a risk-averse middle-management structure seems to emerge that mirrors peoples' class relations in the wider world. If there's some high profile counter-examples you know of please do let me know in the comments!

As groups grow, some people inevitably assign themselves the role of critic or middle manager, never contributing anything positive but always there to give their opinion or “raise some concerns”, and ready to flex their implied veto right. This has been the most extreme in cases where I've seen mid-career academics bring in their PhD students and reproduce the whole student-teacher supervisory relationship in a context that's explicitly meant to subvert that, acting as if they are everyone's academic supervisor rather than an equal member of a non-heirarchical group. Again, never is this dynamic really discussed, as we're a consensus based group right?

What I've found with places that eliminate hierarchies is often informal hierarchies appear, which as an autistic person I find hard to navigate because it's all unwritten and undefined. The other issue, is that for onboarding new volunteers, a lack of hierarchy is really challenging, and only suits a particular kind of person (generally those who are self-starters), otherwise having to engage with the whole structure, rather than the part of it you fit in, is overwhelming and we lose people (we did exit interviews after we lost a bunch of volunteers from Trans Pride Manchester we were working with – the feedback was basically "this whole thing is chaos, I've no idea what you actually want me to do and that makes it impossible to do anything" because we didn't want to assign tasks or anything like that)

– Chris, GFSC Discord, March 2024

Chris' experience is very familiar to me. Back in the days I mostly helped organising feminist and queer festivals, you'd have this pattern of having a kickoff meeting that would have about 30 people turn up, at which 3-5 people would have a discussion while most stay silent, and then over the following weeks see most people drop off and result in an implicit ‘core team’ of two or three. Nothing about this seemed to change the insistence we were using consensus decision making, and only raised some slight sadness wondering why people didn't return (and noone bothered to ask). Essentially we were assuming that this was a normal level of drop-off from an initial expression of interest to the people who wanted to carry on.

Kassey had some experiences with military simulator (‘milsim’) communities that provides an interesting contrast.

The left demonises the idea of violence - and specifically, leaves militaristic utility - to its own harm, because there are so many useful tactics and resources contained within that tradition. The military has a legitimate tradition of legitimate progressivism, leftism and radical politics and there is a massive, underutilised pool of people who thrive in those environments. (If you're interested in learning more, consider looking through here where a vet reads through old American conscript movements - which were anti-racist, intersectional, and wildly aspirational.

– Kassey, GFSC Discord, March 2024

I've never really considered this dimension at all, but it is weird for a social movement that frequently praises left wing armed resistance in other countries, we have such poor connections to veteran and ex-military communities in the UK. Many people I speak to in the movement have family or personal history of being in a range of different conflicts, but this only ever comes out over a few pints and not as part of our movement politics. Honestly, most of the organising I see in use looks like exactly something out of the CIA Simple Sabotage Field Manual, – designed to create as much process-for-process-sake and weak points as possible for no clear organisational gain.

General Interference with Organizations and Production

(1) Insist on doing everything through “channels.” Never permit short-cuts to be taken in order to expedite decisions.

(2) Make “speeches.” Talk as frequently as possible and at great length. Illustrate your “points” by long anecdotes and accounts of personal experiences. Never hesitate to make a few appropriate “patriotic” comments.

(3) When possible, refer all matters to committees, for “further study and consideration.” Attempt to make the committees as large as possible — never less than five.

(4) Bring up irrelevant issues as frequently as possible.

(5) Haggle over precise wordings of communications, minutes, resolutions.

(6) Refer back to matters decided upon at the last meeting and attempt to re-open the question of the advisability of that decision.

(7) Advocate “caution.” Be “reasonable” and urge your fellow-conferees to be “reasonable” and avoid haste which might result in embarrassments or difficulties later on.

(8) Be worried about the propriety of any decision—raise the question of whether such action as is contemplated lies within the jurisdiction of the group or whether it might conflict with the policy of some higher echelon.

– CIA Simple Sabotage Field Manual, 1944

Does all this sound familiar to you? Because it does to me! I don't know how much there is to learn from what amounts to basically the opposite of consensus decision making but I think at least it's an interesting consideration.

Reason 3: it becomes nearly impossible to contribute specific or specialist labour

Perhaps the most serious side effect of the middle management vacuum is that consensus groups don't feel good to do specialised labour in. Because the goal of groups is to get everyone to agree in meetings on a course of action, and work isn't done to establish trust, any specialist skill has to pass a kind of death-by-committee stage where people who know nothing about a thing are given equal weight as the person who has spent their whole life learning a dicipline. The presence of a skill, rather than being seen as a net positive for the group people are greatful to have, almost becomes a threat, a form of power the person has over everyone else. Sometimes people will even suggest “skill sharing” can be done for this person to condense their extensive experience into a workshop they deliver for free in a couple of hours. Needless to say, it's not a very fun environment to deliver work in.

In the example I gave above of organising feminist and queer events, a lot of people came to those first meetings who just wanted to help out with the graphic design, or the website, or the live sound, or some other aspect, but had neither the time nor interest in attending a weekly meeting for 6 months in order to be ‘allowed’ do to so. In fact, one of the only things I got involved in in this era was the exception to this rule, when I turned up to the first meeting, said “I'll make you a website”, then had someone bite my hand off a month later and work on it with me. This was I think the only time this has happened in my entire history in these groups!

Generally 1-3 people in any given group end up doing the actual work, and if you're lucky another 3-5 are willing to do tasks if actively managed to do so by one of the core group. As groups develop they get an increasingly large group of people who like being culturally associated with the space, who perhaps did a task once a year ago and are still on the email list, and see themselves as part of the group: but often have contributed no labour or just a few hours a long time ago. Equally, new people can be a lot of work to manage and sometimes come with unrealistic expectations. Yes, this is one way the movement as a whole grows in capacity, but the labour to do this people management is largely unrecognised and gets swept under the rug.

Even worse, the people who do this labour end up getting put up on pedestals as examples of “good” activists, and given more unpaid work to do, becoming de facto but unrecognised spokespeople for the group, on the fast track to burnout as more and more choices get routed through them with little support given other than lip service. I think everyone I know who has ended up in this position has both hated it, and burnt out in short order.

More from our Discord discussion:

With Trans Tech Tent, I used to do a lot of pick ups / drop offs of tech, and it was like... 5 minutes out of my day, every few weeks. Sometimes more, sometimes less. But I honestly think that having that routine, easy, mindless job was good for me and the org -- it meant that the group was getting really essential stuff from me, but it also meant that I knew what the basic functioning of our system was.

– Kassey, GFSC Discord, March 2024

I have never found a consensus-based group able to offer these kinds of opportunities. My closest experience to Kassey's was helping to set up Taphouse TV Dinners, a free meals-to-your-door service that we developed at the start of Covid-19 that has now served over 10,000 meals out of a local community pub kitchen (sadly, the pub has now shut down due to rising costs). Here, a load of us chipped in: I made a database in Airtable that got info to and from where it needed to be, ACORN set up volunteers for deliveries, and the pub handled the ingredient sourcing and cooking. Someone drew a logo and someone else made a newsletter. I don't think any of us ever saw it as anything other than helping out the pub with their idea though: we all just kind of intuitively knew it was their project and we were just helping out.

I think this service would simply have not got off the ground or continued to be a success if we were running it via consensus: it worked precisely because it allowed people to turn up and do a delivery now and again and not have to do any more work than that. It worked because two people (Rachele and Shakira at the pub) were taking final responsibility for the labour and making the project run, and just asked other people for help as they needed, and everyone just trusted everyone else to get on with it.

Reason 4: feminised labour is taken for granted

Perhaps the worst part of insisting that everyone has consented to everything is that they tend to obfuscate what the labour in a group actually is.

Most of any groups' labour overall is reproductive labour: organising and hosting meetings, managing email lists, keeping minutes, resolving conflicts, looking after people, the infrastructure that makes doing things possible. But most groups' stated function is productive labour: making and doing tangible things. Overwhelmingly, women and femmes end up doing the lions' share of the reproductive labour and men are only interested in the productive labour.

I've literally run community cafe events before where all the women and femmes were in the kitchen doing the washing up and cleaning the floor and getting ready to get out the building, while the men were in the main area standing up, pointing at each other and talking loudly about Marx or something, completely oblivious to the cleaning that was going on around them. I've seen senior men academics yell at people on the community centre email list because they wanted to show a film about oil and the women and queers hadn't cleaned the space up to their exact specification when they arrived. It's everywhere, and it's so gross.

Somehow, all this labour is seen as out of scope for the group itself. Rather than have everyone contribute towards maintaining a space together, we end up with women and femmes facilitating spaces for men to see their vocal contributions and implied veto in meetings as the function of the group itself. Again, we have recreated wider patriarchal structures in miniature. Good job, us.

Final thoughts

So, what we have as a default and rarely challenged modus operandi is a bit of a cultural and organisational mess that combines a very specific project management methodology that most people have no experience in with a very specific political ideology that most people don't have experience putting into practice. Often, these contexts are the first time people have any real power over anyone else, and have their choices taken seriously. Fundamentally, thinking as an equal participant in a group and not a service user is a huge shift and most people are not exposed to spaces where this is even an option.

The last decade or two has seen peoples' conception of organising go from something that necessarily takes place in a physical building, to one that primarily sits online. When we had to have physical spaces there was a certain logic to this which was self-evident: of course we need to keep the doors open and feed everyone. You could be involved without knowing the slightest thing about poltics. Now we've shifted to a culture where people's primary engagement with politics feels more like just reacting to things you see online. It's far, far easier to comment on things than to actually do things, especially now venues are folding like flies, everyone's knackered and burnt out, squatting is a lot harder in the UK than it was, and the cost of living is too too high.

I think the last thing we need when we do get the energy to go and be involved in something is to have to go and debate a stranger in order to be allowed to do so. We need people who show up to be able to just get stuck in doing something meaningful that they enjoy, for reproductive labour to be recognised and valued, and for our input to not immediately get overturned the next week. Having veto power over a group from day one is stressful, innapropriate, and disrespectful of the people who put their time into maintaining the space. Consensus is great, but lets get there through doing fun things together where we get to know each other and form friendships, not through having more fucking meetings. Unless you do already know each other and actually love meetings. In which case you do you.

What do I suggest instead? That'll have to wait for next time. Community Rule is a great website that has some ideas. I like do-ocracies, but I think the important thing is to pick something suitable for the group. Overall my advice for new organisers is to keep it small and sustainable. Never plan to grow a group past say, five people: do something with your friends, keep it small, keep it specific, keep it local, and network with other groups rather than trying to do everything yourselves. We're developing our own method to facilitate this as part of the Community Technology Partnership approach based on this critique and will be updating the blog with it as we go.

The tl;dr of this piece is the ever excellent quote:

NO ONE WAY WORKS, it will take all of us

shoving at the thing from all sides

to bring it down.

– Diane di Prima

No one way works. I might get it tattooed.

Comments ()