How GFSC got to here (Part 1)

Behold, a mythic lore drop from studio founder Kim. Read her never-before-told-story (at least, outside the pub) about the various elements floating in the existential stockpot that slow-cooked GFSC's primordial soup.

Hi, I'm Kim and I started the thing that became GFSC back in about 2015. I've told bits of this story a lot in person but never committed it to page, so I think maybe it's about time as we launch the current phase. GFSC roughly speaking has three phases: from 2015-2020 when it was just the name for my freelance practice and activism; from 2020-2024 when I won a couple of big funding bids and attracted core funding which has sadly now all ceased; and starting properly in 2025 the new phase, which you can read about on the intro post. This has grown to be kinda long so I'm just going to tell the first part today!

My origin story

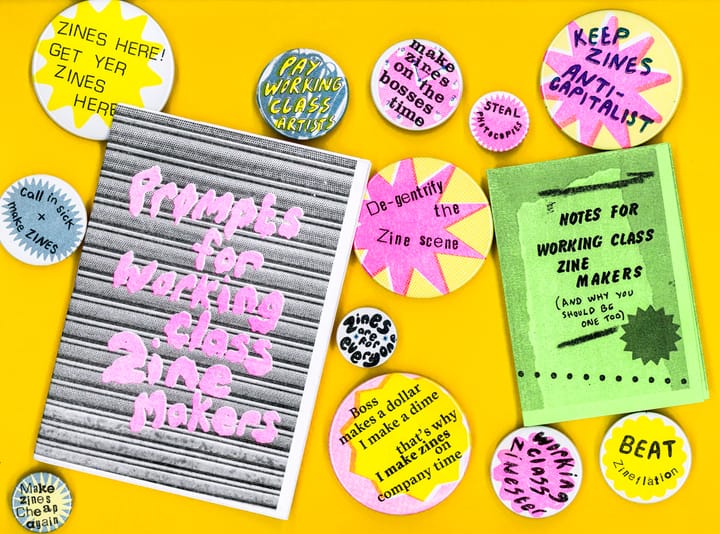

The origins of GFSC started from the three main things I was doing in the late noughties and early teens: a PhD, website work for grassroots groups and artists, and most of all being involved in DIY, punk, feminist and activist movements.

My heart has always been with DIY scenes. This started in Nottingham's DIY punk scene where I ran a record distro and was in a couple of bands that never went anywhere. I then moved to Leeds, ostensibly to top up my HND into a degree, but really because I'd been on Indymedia and saw there was loads of political activism and queer stuff going on there and it just felt like the right place to be, a nice contrast to the apolitical, cliquey and utterly straight white guy-dominated music scene that dominated Nottingham. In Leeds I got plunged directly into communities of direct action, squats, social centres, allotment sites, mass protests, and most of all the Queer Mutiny movement.

Queer Mutiny was probably life changing for me in many ways – baby queer me was certainly not ready for it! But for about 3 years I lived in a giant squatted social centre and put on a ton of events (including inadvertantly founding Leeds Queer Film Festival, I later discovered). My main contributions were live sound (when I was more able-bodied) and making websites for things (when I wasn't). Most of all though, and I can't stress this enough: I thought this was normal. This just seemed to be to be what people did after uni in that place in the world at that moment in time. Why would we pay rent and get a job if we don't have to? I think if I'd never had that early education in the idea that you can just make the world you want to live in if you put your mind to it, I'd never be the person I am today.

The PhD was about soundscapes, which are basically the acoustic counterpart to landscapes, all you can hear rather than all you can see. I don't have much to do with this any more but I learned so much, mostly about how to communicate qualitative research to fields that prioritise quantitative research, and vice versa, being split as I was between the acoustics and sociology department. I think most of all what a PhD gives you is a real appetite for big, chunky, complex real-world problem solving, and the feeling for what the various stages of a multi-year year project feels like. I also made a bunch of weird art around this which was fun to do and I'm sad I never followed up, but I couldn't really shake the feeling of not being a “proper” artist I suppose, as someone split as I was between multiple worlds (something I'm now slowly returning to).

Website work was a way to make ends meet while doing all this, I had to go part-time on the PhD for health reasons but then wasn't making enough money. I'd always made websites but I ended up getting a bit of contract work first for an "ethical" design studio (whose "ethics" mostly seemed to be that they had clients who considered themselves ethical, if I'm honest – there was nothing ethical about the studio itself), then a friend I met doing this work. I learned a ton doing this and got a lot of my 10,000 hours in, learned how to handle clients myself, and so on. A trial by fire, especially in the era where most tech workers were teams of one having to do everything and before git existed, too.

Living one life, not three

So in 2014 I had just finished my PhD, my website collaborator had moved onto other things, the feminist DIY scene seemed to have crashed and burned (with hindsight I think this was the beginnings of the TERF movement as all of a sudden gender essentialism had slipped into these spaces that wasn't there before), and I was managing a now pretty devastating bout of chronic fatigue syndrome.

Reflecting on my three paths in life so far -- academia, tech work, and activism -- I realised how utterly un-integrated they all were. I also knew I needed to do one thing well rather than three things badly for my health if no other reason. Academia makes big noises about wanting to do community engagement or pursue social goals, but when it comes down to it they're almost completely impossible to interact with from a tech or activist standpoint: the timescales are so long and the institutions have no idea how to behave non-extractively. The tech world simply has too much money in it to have to listen to anyone else and is speedrunning reinventing every subject area in its own image and with its own ultra capitalist ethics: real Emperor's New Clothes stuff.

In developing a new practice, I started from the now obvious realisation that website commissioning was broken. I'd had a few experiences of making something that met a client spec, naively doing everything they asked for, but then when it came time to deliver it back to the client it wasn't quite what they wanted. Every client thinks they'll somehow have time to write a blog, even though they've never written a single blog post. Everyone thinks they'll keep their website updated, but when you log into their painstakingly created custom CMS a year after launch you'd often found they'd never been logged into by the client. Why are we collectively making life hard for ourselves? How come everyone demands features that require work they don't actually want to do? Surely there's a better way?

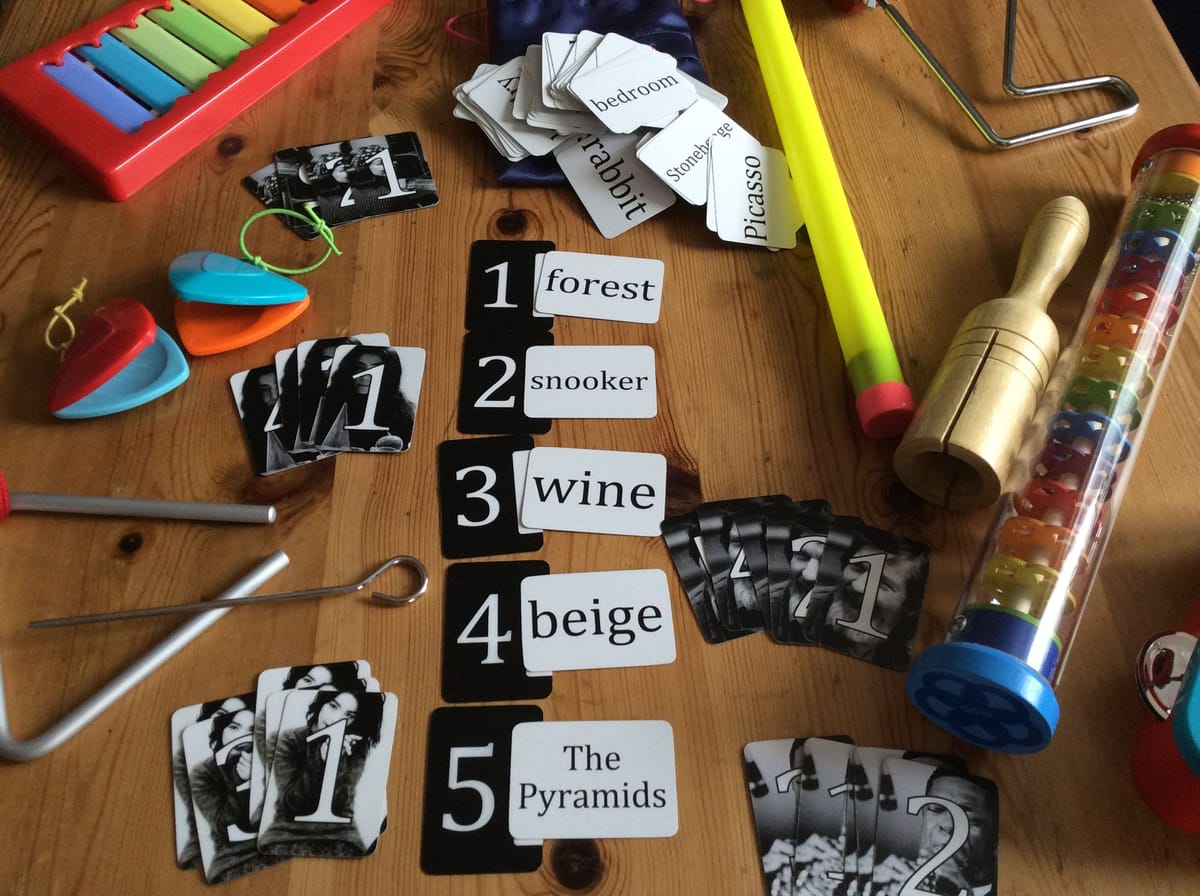

In 2015 I meet Mark, now GFSC resident designer, and we volunteered together on the First National Festival of LGBTQ History, which was let's just politely say a ... mixed experience (a story for another day); with hindsight this was the first "GFSC-y" thing I probably did. Without really knowing that's what we were doing at the time, along with a handful of friends we took on this overarching role of everything from brand guardianship to festival coordination to managing bookings and ticketing. Notably, the website was the first one I'd made trying to use existing things we already were using – in this case Google Calendar – to power the events listing page. With a dozen or more people constantly updating the program in the weeks leading up to the event, it was essential that everyone could update it as simply as moving things around in a Google Calendar, so I made a set of scripts that downloaded the iCal feed from each venue and then compiled it into HTML. This inadvertently became the proof of concept for PlaceCal, which we will get onto later.

The rise of the tech sector

My timeline is a bit wonky (poss its about 2016 now?) but it's about this point I organised an IRL meetup, called Geeks for Social Change, the first emergence of that name! Through it I discovered quite how little knowledge there was in the tech scene at the time about things like qualitative research methods, ethics outside of tech ethics, sociological means of enquiry, etc. Through this work I ended up working on Street Support, a directory of homelessness services, and was able to nudge them from being an app that let people donate to individual homeless people on the street via an app to a more holistic approach working with homeless services to help everyone work better together. It's now active in nearly 30 cities and I'm really glad I was able to steer this at the initial stage.

The weirdest thing about this experience though was the context. Street Support had won startup funding from a tech accelerator. This was based in a pretentious coffee shop (it had a floor to ceiling oil painting of Walter White from Breaking Bad in the entry way), sponsored by a "tech for good" startup venture capital fund, sponsored by a bank. The whole setup was deeply weird -- the coffee shop itself was a strange liminal space, part expensive coffee, part co-working space, part bank office? Most of the other startups that got funded to me seemed to conflate "tech for good" with "make money from poor people", tbh a critique which has never really gone away. Doing the footwork on this was a jarring experience, alternating being on a 15th floor tech meetup in the Thoughtworks office sitting in rows of £1,500 office chairs helping ourselves to the free pizza and sushi buffets (and there's wine in the fridge if you want), to meetings in unheated, falling down community centres that havn't been refurbished in decades struggling to keep the lights on with just tea and instant coffee. These buildings were a stones throw apart, ostensibly working on the same issues, but wow -- just worlds apart.

This experience made me realise that when it comes down to it, the real tech world innovation is the startup itself, a unit of investment that allows rapid prototyping of business models that involve an vertically-integrated "app" that has the potential to be as profitable as possible; any allusions to community or research are solely in the context of market research to increase turnover. In activist contexts (my life-long love/hate relationship), while it feels home to me in many ways, it's also the only place I know people are being really real as there's no other reason to do something that gives you no status or money and is very stressful, wow people are grimly hung onto 20 year old strategies. While in some ways it's better now due to the influx of gen-z, I've lost track of how many times I've had to convince people (usually academics) that having a nice logo and good website isn't just a 'nice to have', its literally essential if you want to engage anyone but other people who look exactly like you.

Reading books is good for you

The final step before GFSC-the-studio was the Ethics and Technology Reading Group I ran from about 2017-2020 (we stopped at the beginning of the Covid pandemic). Starting with Ursula Franklins' The Real World of Technology, an essential listen / read for all working in the tech sector, we met up to discuss a text every month for about three years. At some point I should publish what we read from this but this little group of people helped me move my thinking forwards so much in terms of thinking about what technology even is, and how we might want to integrate it into our lives. I think without this intense period of reading and reflecting on the history and culture of technology, I wouldn't have started any of this.

Kim and two other members of the ethics and technology reading group in 2019

I wrote an essay called “Tech culture is failing communities. How can we make it better?” around this point on the precursor to the current GFSC site. This helped me direct all the thoughts about the reading group and went somewhat as viral as possible as it was for a piece like that to go at the time. Possibly because of this or possibly not I got introduced to Prof Stefan White at MMU, who was looking for someone to work on a platform called PlaceCal... which if you're following us I hope you've heard of!

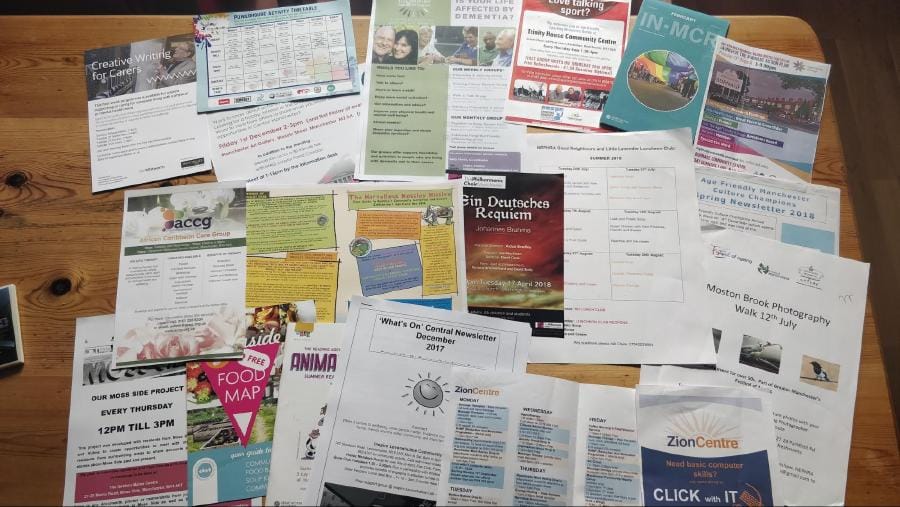

Stefan was super frustrated because through his Manchester Age Friendly Neighbourhoods team, they'd identified that basically what was needed was some kind of way to automatically import calendars that the community groups were creating but all in one place. They'd got some funding from a "smart city" accelerator called CityVerve that was investing in tech prototypes that just happened to be where we were all based. You can read about PlaceCal in loads of other places but I think of note was that Stefan couldn't find anyone in the uni or the wider CityVerve cohort to work with as they all thought this was too boring, and were looking for something exciting to do with GIS or AR (Augmented Reality) or IoT (Internet of Things), the hype techs at the time. So we ended up getting to work together through this low tech, high social engagement approach. Ironically of course, I think PlaceCal is the only surviving platform from the entire 10m CityVerve project.

Left: the mess of community information PlaceCal addresses. Right: our Winter 2017 launch party.

This takes us up to about 2020 and Part 2 of this story, which we will save for another day.

The GFSC homepage has a Venn diagram on showing these three segments that was drawn up almost on day one of thinking about the project as a whole. Honestly I still don't think I've really worked out how to bridge any of these overlaps in concrete ways. Starting this new phase though has encouraged me to go back and reflect and work out what potential there is now, almost a decade later.

Have you tried to combine disperate worlds into one practice? If you work in community tech, how do you fund your work? Have you found ways of making things in the gaps?

Comments ()